[See part I: Introduction.]

To assist in identifying “the restrainer” we might scan through the first chapter of 2 Thessalonians for possible points of contact. At least one commonality is found below.

First, I will translate 2:1–9, even though we’ve yet to explore other interpretive avenues for 6–7. One available option is evident in the forward slash ( / ) between two alternatives. Elsewhere, the grammar and syntax allow other renderings. Explanations will follow further below. Greek words repeated in the text are bracketed and in colored font for easy reference and comparison.

2:1 Now, dear brothers and sisters, regarding the coming [Parousia] of our Lord Jesus Christ and our gathering together to Him, we ask you 2 not to be easily troubled in mind or alarmed by any spirit, message, or letter, seemingly from us, to the effect that the Day of the Lord has already begun. 3 Let no one deceive you in any way, for ⸤ that Day will not begin ⸥ unless the rebellion comes first, and the man of lawlessness is revealed [apokaluptō], the son of destruction, 4 the one opposing and exalting himself above all that is called ‘God’ or ‘object of worship’, such that he seats himself in God’s sanctuary, proclaiming that he himself is God. 5 Do you not remember that when I was still with you, I was telling you these things? 6 And now you know what restrains[nt] [(him)], that he may be revealed [apokaluptō] in his/its[ms/nt] season. 7 For the mystery of lawlessness is already working, only until the one who/which now restrains[ms] becomes out of the middle. 8 Then the lawless one will be revealed [apokaluptō]—whom the Lord Jesus will destroy with the breath of His mouth and extinguish by the radiance of His coming [Parousia]— 9 which is the coming [parousia] according to the working of Satan . . .

Few would find Paul the model of clarity in 2 Thessalonians 2. Besides the run-on sentences and digressions, he even leaves out part of the sentence in v. 3!7 The italicized text between the subscripted brackets ( ⸤ ⸥ ) fills it in.8 Paul also deviates from the plural “we” used throughout this epistle (…we ask you…), to the singular “I” in his digression of 2:5 (…when I was with you, I was telling you these things?).

Grammatical and (Inter-)Textual Considerations

Note the repetition of both Parousia and apokaluptō. On the former (Parousia), Paul uses it twice to refer to Jesus (v. 1, 8) and once to “the lawless one” (v. 9—illustrated here by the use of lower case parousia). Paul contrasts the ‘coming’ of the lawless one with the coming of our Lord Jesus Christ. He juxtaposes the lawless one’s counterfeit parousia with Christ’s true Parousia.9

Regarding apokaluptō, this word is explicitly used twice in reference to the lawless one (v. 3, 8) and once seemingly to him (v. 6). Yet, v. 6 is in a different verbal form (infinitive10) than the others. Interestingly, the noun form (apokalypsis) of this verb signifies Jesus’ revelation in 2Thess 1:7.11 Larger context better illustrates:

1:5 …proof of God’s righteous judgment that you will be considered worthy of the Kingdom of God, for which you are suffering, 6 since it is a righteous thing for God to repay those afflicting you with affliction, 7 and to you who are being afflicted with relief with us, at the revelation [apokalypsis] of the Lord Jesus from heaven with angels of His power.

Paul pastorally comforts the persecuted Thessalonians by assuring them that he, Silvanus, and Timothy (1:1) will join them in their relief at Jesus’ revelation, aka Parousia (2:1, 8). Chapter 1, then, serves as a preface to his correction in chapter 2.

Paul specifically uses apokaluptō for the counterfeit parousia. That is, in 2:8–9, he defines the lawless one’s “revealing” by parousia. If we remove the portion of v. 8 referring to Christ’s Parousia (between the em dashes), we are left with: “Then the lawless one will be revealed [apokaluptō]…which is the coming [parousia] according to the working of Satan…”

Zeroing in on 6–7, we must first mention the verb katechō. At root, it carries the meaning “hold”, though in translation we may further nuance it according to context. Yet it may be important to keep this basic definition in mind, for this could foster out-of-the-box thinking in our subject verses.

The New Testament (NT) uses the word in a variety of ways, with “hold” underlying each occurrence:

-Luke 4:42: crowds were holding [keeping, detaining, delaying] Him, that He not depart from them

-Luke 14:9: in shame, you would begin to hold [occupy] the lowest place

-Acts 27:40: hoisting the mainsail to the wind, they began holding course [heading] towards shore

-Rom 1:18: the wrath of God is revealed against men who hold back [suppress] the truth

-Rom 7:6: having died in that which we were held [bound, confined]

-1Cor 7:30: those buying (things), as if not holding [possessing, owning] (things)

-1Thess 5:21: hold [hold fast, cling] to the truth

This briefly summarizes NT applications, providing fodder for possible alternate renderings in 2:6 and 2:7.

In v. 6, note “him” in brackets. The verb for “restrainer”, katechō, can be understood as acting either intransitively (without accusative direct object) or transitively (with direct object). Either interpretation is possible here. If we assume the word is functioning intransitively, then we simply end the clause with “what restrains” and leave it at that.

If transitive use is assumed, then we supply the direct object from context—“him” in the tentative translation above. Luke 8:15, in which the transitive is surely implied, exemplifies: and having heard the word, they hold [katechō]. In this verse, katechō has no expressed direct object, so translators follow “hold” with a supplied “on to it” (“it” referring to “the word”).

No matter how this is interpreted, there is the accusative direct object “that he may be revealed” in the very next clause. In the intransitive application, this clause further explains in some way “what restrains”. In the transitive application, we would then have a double accusative/direct object structure, in which the second one further explains the first in some manner: “…what restrains him, that he may be revealed”.

The verse begins with the Greek kai nyn, “and now”. The “now” can be interpreted one of two ways: temporal or logical. If temporal, it is rendered like the NASB: “And you know what restrains him now”. In other words, ‘you know what is currently restraining him’. If logical, it is akin to the rendering in the above translation: “And now you know what restrains”. The sense is ‘now that I’ve re-explained things (2:1–5), you know what restrains’.

The final clause in v. 6 is ambiguous, in that the pronoun can be either masculine or neuter: “in his season” or “in its season”. If masculine is assumed, the pronoun most naturally refers to “he” in the previous clause. But, could it be neuter? If so, what would be the referent?

At first glance, v. 7 appears to contain a syntactical anomaly. It seems to consist in two separate sentences, the second one missing the main verb. However, the solution is to construe it as one sentence, with word order in the latter portion intending to emphasize the subject (“the one restraining now becomes…”) of the dependent clause.12 The effect would be to understand “only” and “until” as a consecutive unit, despite the Greek having “the one restraining now” sandwiched between the two. The International Standard Version (ISV), e.g., renders it in this manner: For the secret of this lawlessness is already at work, but only until the person now holding it back gets out of the way.

The first part of the sentence—the main, independent clause—is relatively straightforward: “For the mystery of lawlessness is already working”. The final phrase ek mesou genētai (ἐκ μέσου γένηται, “out of the middle becomes”, “from the midst becomes”) in the dependent clause, however, has occasioned some difficulty. This exact phrase is absent in the NT. Though the verb (from ginomai, “become”, “come to be”) is very common, ek mesou occurs only a handful of times. Excluding 2Thess 2:7, here are the NT ek mesou occurrences:

-Matt 13:49: The angels will…separate the evil ones from among the just

-Acts 17:33: Paul went out from the midst of them

-Acts 23:10: snatch him [Paul] from the middle of them

-1Cor 5:2: removed from the middle of you

-2Cor 6:17: come out from among them and be separate

Each of the above is, essentially, “from the middle/midst” or “out of the middle/midst”, though context may favor slightly different wording in English. The meaning is very much the same, however.

Some have tried to interpret this final clause using “the mystery of lawlessness” as the subject of “becomes out of the middle”. However, “the one who/which now restrains” is certainly the subject. The capable F. F. Bruce refutes such a notion:

Attempts have been made to construe the clause as though the reference were to the mystery of lawlessness “coming to pass out of the midst”—i.e. emerging from its place of concealment, but that would require εἰς μέσον [ED: accusative] not ἐκ μέσου [ED: genitive].13

Excursus: Becoming out of the Middle

To further assist in exegeting ek mesou genētai, “out of the middle becomes” we will compare this phrase with a very similar one (same verb but different form) in a Greek romance, likely composed in the 2nd century AD. The selection below is from Achilles Tatius’ Leucippe and Clitophon.

To set the stage, Clitophon and Leucippe become attracted to each other after circumstances place the latter in the former’s household in Tyre. After a time, the two conspire to partake in a nighttime rendezvous in her [Leucippe’s] chambers, with the assistance of household servant Satyrus and Leucippe’s personal maidservant, Clio. On that night, moments after Clitophon lies down in her bed, Leucippe’s mother, Panthea, awakens from a nightmare, provoking her to run to her daughter’s room. Upon seeing the silhouette of a man in Leucippe’s bed, Panthea erupts in hysterics. Under cover of darkness, Clitophon escapes, eventually making his way to his room, unsure if Leucippe’s mother recognized him as he fled. He assumes the worst.

Panthea interrogates Leucippe and Clio [her maidservant] in order to determine the identity of the nighttime visitor. In this, Panthea reveals that she did not realize it was, in fact, Clitophon in her daughter’s room. With this knowledge, Leucippe lies to her mother, saying she did not know the identity of the man. Meanwhile, aware of Panthea’s revelation to her daughter, both Clitophon and Satyrus plan to flee before the entire conspiracy is exposed. With this plan conceived, they proceed to the house of Clinias, Clitophon’s cousin, in order to further prepare.

Soon after, Clio arrives at Clinias’ house, desiring to escape from her sure interrogation by torture come morning. With this, she informs Clitophon, Satyrus, and Clinias that Panthea was as yet unaware of the identity of Leucippe’s visitor. Upon hearing this, Clinias pulls Clitophon aside, suggesting they secretly and swiftly send Clio off, out of harms’ way. This would provide the opportunity for Clitophon and Satyrus to persuade Leucippe into fleeing with them, as well.

Following is Clinias’ reasoning in suggesting to Clitophon that Clio be sent away. First is the Greek, which is followed by a word-for-word working translation, then a more readable rendering:

Achilles Tatius, Leucippe and Clitophon, 2.27.2:

Οὔτε γὰρ νῦν οἶδε τῆς κόρης ἡ μήτηρ τίνα κατέλαβεν, ὡς ὑμεῖς φατε,

ὅ τε καταμηνύσων οὐκ ἔσται τῆς Κλειοῦς ἐκ μέσου γενομένης:

τάχα δὲ καὶ τὴν κόρην συμφυγεῖν πείσετε.

And-not for now she-knows, the girl’s (the) mother whom she took, as you spoke,

that but will-make-known not be (the) Clio’s out of the middle becomes.

Perhaps now and the girl flee-along-with you-persuade

“For now, the girl’s mother [Panthea] does not know whom she saw, as you said,

and there will be no one to inform her when Clio becomes out of the middle.

And then perhaps you could persuade the girl [Leucippe] to flee with you.”

Clio is currently caught between Leucippe and Leucippe’s mother, Panthea. She does not want to divulge the conspiracy, thereby incriminating herself, Leucippe, Clitophon, and Satyrus; yet, Panthea, who wants to know the identity of the night visitor, will surely attempt to torture her for the information. By following Clinias’ suggestion, Clio would become out of the middle.

Her escape would also buy some time for Clitophon and Satyrus to persuade Leucippe into fleeing with them all.

To restate, following Clinias’ suggestion, Clio would no longer be in the middle of the situation—in the middle between Leucippe and Panthea. She would become out of the middle, removed from the entire situation. Yet, note that it is Clio’s escape that makes her become out of the middle. In other words, her escape is the means by which she becomes out of the middle. It is not some external force removing her—with help from the others, she removes herself (“becomes out of the middle”) by escaping.

We might render the above, “and there will be no one to inform her when Clio escapes”. But, this would fail to retain the poetic value of the original “becomes out of the middle”. We must be careful not to over-translate when rendering texts, thereby imposing our own interpretation upon it.

Application

Applying this excursus to 2Thess 2:7, the overarching point is that the exegete should not be constrained by the common English versions, which use verbiage such as “is removed”, “is taken out of the way”, or “gets out of the way”. It is prudent to begin with the ‘bald’ translation “becomes out of the middle”. To the extent possible, begin with a tabula rasa, a clean slate. Reach an exegetical conclusion only after considering all grammatical and contextual options.

In v. 7, the verb “becomes” can be either passive or middle. If passive, some external force/person provides the action. If middle, ‘the restrainer’ has some part in becoming out of the middle.

Considering the context of v. 8, we know that once “the one who/which now restrains” becomes out the middle, the result is the revealing of the lawless one.

Opened Avenues

Within the framework provided by this part of the current series, one can begin to explore other exegetical possibilities, unencumbered by the usual interpretations. The next segment will provide one such alternative: An Alternate Angle.

___________________________________________

7 Many would argue there is also an ellipsis in 7b, requiring the addition of a finite verb to complete it. However, it is possible ἕως, eōs (“until”) is placed postpositively, after ὁ κατέχων ἄρτι, ho katechōn arti (“the one who/which restrains now”) in order to emphasize “the restrainer”. Assuming so, 7b should be understood as a dependent clause to “The mystery of lawless is already working” instead of a separate sentence. This is the approach taken above. See, e.g., Charles A. Wannamaker, Commentary on 1 & 2 Thessalonians, NIGTC (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1990), pp 255–256.

8 More specifically (and technically), v. 3 is missing the apodosis, which is the main (independent) clause in an ‘if-then’ conditional statement. Only the protasis, the dependent clause, is stated here (“unless [‘if not’] the rebellion comes first and…”). In other words, in the case of vv. 3–4, it is the ‘then’ part that is absent. It is probably best to place the ‘then’ in the beginning of the sentence—as most English versions do—though it can be appended to v. 4, which would yield: “…proclaiming that he himself is God, [then] that Day will not begin.” See Young’s Literal Translation (“…the day doth not come.”).

9 Relatedly, see this post Not One Parousia, But Two.

10 More specifically, it is an articular infinitive within a prepositional phrase, indicating result. See Rodney J. Decker, Reading Koine Greek: An Introduction and Integrated Workbook (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2014), pp 368, 372.

11 This same noun is used to begin the final book of the Bible, Revelation: The revelation/apocalypse [apokalypsis] of Jesus Christ…

12 See note 7 above.

13 F. F. Bruce, 1 & 2 Thessalonians, Word Biblical Commentary (Waco, TX: Word Books, 1982), p 171.

It's Appropriate To Share:

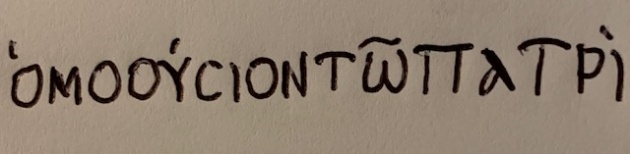

The accent over the first omicron (O) is what is known as the rough breathing mark, indicating to sound the vowel with a prepended English “H” (“ha”). This is the reason for its transliterated spelling homoousion.

The accent over the first omicron (O) is what is known as the rough breathing mark, indicating to sound the vowel with a prepended English “H” (“ha”). This is the reason for its transliterated spelling homoousion.

Recent Comments