What does “church” mean to you? Would it surprise you to learn that the underlying Greek term we translate “church” in most Bibles is much more accurately summoned assembly or congregation? The term in its original New Testament (NT) context referred strictly to persons called to a specific assembly (Christ-following)—not to a physical structure, much less to some hierarchical, institutional structure.

The word “church”—and the capitalized “Church”—is weighted down with too many misleading and negative connotations. Consequently, like an Olympic shot putter, it’s high time we hurl it into the field!

But how did “church” get applied if that’s not even what the word means?

What Do You Mean That’s Not What it Means?

The word translated “church” is the Greek ekklēsia. It is formed by the preposition ek, which means “from” or “out of”, plus klēsis, a noun. Klēsis means some sort of special call, calling, invitation.1 Thus, in a general sense, ekklēsia is defined as a group summoned from a larger group, an assembly called out of a larger people-group.

But does the word itself connote some special significance in the NT? More specifically, does the term refer exclusively to Christ-followers? To answer this, we’ll need to look at how this term and its cognates are used in the NT.

The NT records klēsis only eleven times. Each use refers to either the calling of Christ or a calling of God: Rom 11:29; 1Cor 1:26; 7:20; Eph 1:18; 4:1, 4; Phil 3:14; 2Th 1:11; 2Tim 1:9; Heb 3:1; 2 Pet 1:10. In this sense, it bears special significance.

Its adjectival form, klētos, is used ten times,2 in somewhat similar fashion: Matt 22:14 (in a parable); Rom 1:1, 6, 7; 8:28; 1Cor 1:1, 2, 24; Jude 1:1; Rev 17:14. Thus far, the evidence could go towards supporting Christians as exclusive ‘called-out’ ones.

Jesus summoned his first disciples (Matthew 4:21 [cf. Mark 1:20]) using the associated verb:

…kai ekalesen autous

…and He-called them.

…and He [Jesus] called them.

The root of the verb used above is kaleō, which means to call, summon, invite, call by name. This is a very common verb, found 140 times (in its various forms) in the NT. Though it is used for the calling to Christian discipleship, this verb also applies to the naming of John the Baptizer (Luke 1:13), identifying the name of a city (Luke 7:11), etc. Thus the word is not purposed exclusively for summoning Christians.3

But maybe we should focus strictly on ekklēsia?

Calling the Ekklēsia

The LSJ, the most comprehensive lexicon for Ancient Greek literature, defines ekklēsia (ἐκκλησία) generally as an assembly duly summoned. The term is found in Homer and other ancient Greek writings well-predating the NT. It can refer to political, legislative bodies governing the populace for example (see Aristotle, Athenian Constitution 43.4). Though some have seized upon this latter meaning, attempting to apply it to Christianity, this is clearly not how the term is used in the NT. Scripture gives no indication that Christians are to rule over non-Christians. On the contrary, Christ-followers are to be servants. In any case, given the usage of the term pre-NT, the word clearly wasn’t coined specifically for Christians.

The term is used 93 times in the LXX (aka Septuagint)—the Greek translation of the Hebrew Tanakh, the Old Testament (OT). Though many times ekklēsia refers to Jews in religious contexts in the LXX, it is not used solely in this way. It also references: a group of Jews in a political sense (Deut 18:16), a specific assemblage of returned Jewish exiles in distinction from the larger group of Jews generally (Ezra 10:7-8), and even a pack of evildoers (Psalm 26:5 [LXX 25:5]).

The NT records the term 111 times. The very first usage is in Matthew 16:18, in Jesus’ words to Peter:

…kai epi tautȩ̄ tȩ̄ petra̧ oikodomēsō mou tēn ekklēsian

…and upon this the rock I-shall-build my the ekklēsia

…and upon this rock I shall build my ekklēsia

Putting aside any discussion of the enigmatic “upon this rock”—which is beyond the scope of this present article4—what does ekklēsia mean here? [The extra ‘n’ at the end of ekklēsia in the Scripture is to denote the accusative form, direct object.] Might Jesus mean my ‘called-out’ ones? Let’s investigate further.

The Apostle Paul uses this term in the beginning of some of his epistles. An example is found in 1Thessalonians 1:1: …to the ekklēsia of the Thessalonians. The ekklēsia at Thessalonica. In Acts 8:1, which speaks of the aftermath following the stoning of Stephen, there was great persecution against the ekklēsia at Jerusalem—against the group of Christ-followers in Jerusalem. Yet, before this persecution, Stephen, in the midst of his speech to the Sanhedrin, recalls Moses who was in the ekklēsia in the wilderness with the angel who spoke to him at Mount Sinai (Acts 7:38). This latter usage clearly refers to Jews in an OT context, not NT Christ-followers. But that’s not the only instance of the term referring to a group identifiably not Christian.

In Acts 19, three successive applications of this term clearly do not refer to followers of Christ: an assemblage of pagans brought together by Artemis the silversmith in opposition to Paul and “the Way” (19:32), some sort of official legislative body (19:39), and Artemis’ group once again (19:40). These three instances, plus Acts 7:38, indicate that this word in and of itself is not some special term used exclusively for Christians in the NT. As with most words, context determines meaning.

The final definition of the term in the LSJ lexicon well-explains its application in the NT as it relates to Christ-followers—as well as its later expanded usage:

in NT, the Church, as a body of Christians, Ev.Matt. 16.18, 1 Ep.Cor.11.22 ; ἡ κατ’ οἶκόν τινος ἐ[κκλησία] Ep.Rom.16.5 ; as a building, Cod.Just.1.1.5 Intr., etc.5

In other words, the LSJ indicates that the term is applied in the NT (except the four exceptions above) to “the Church” collectively as a body of Christians, using Matt 16:18 and 1Cor 11:22 as examples. However, the term was later used as a building, as in Codex Justinianeus (Code of Justinian), from circa early 6th century AD. To this latter meaning we will return further below.

Sandwiched between the two definitions in the LSJ (the Church, as a body of Christians; and, as a building) is a reference to the usage in Romans 16:5. Providing proper context for this verse, to include the two immediately preceding verses:

3 Greet Prisca and Aquila, my coworkers in Christ Jesus 4 —who, for my life, risked their own necks, for whom not only do I give thanks, but also all the ekklēsiai of the Gentiles 5 —and the ekklēsia in their house…6

The basic sentence above is Greet Prisca and Aquila…and the ekklēsia in their house. Here the ekklēsia must be a particular group of Christians who gather at the house of Prisca and Aquila. Thus, a small subgroup of Christians. In verse 4 Paul pluralizes ekklēsia, indicated by the final iota (i): ekklēsiai. By its context, these multiple ekklēsiai are other individual gatherings of Gentile Christians meeting in individual homes in Rome.7 Considering the example of 1Thessalonians 1:1, we can infer that if “all the ekklēsiai of the Gentiles” (16:4) were to be combined with the one ekklēsia at Prisca and Aquila’s house (16:5) this would comprise one larger ekklēsia. In other words, each small subgroup (meeting in a home) is an ekklēsia, and the combination of these individual ekklēsiai (meetings in homes) logically would make up one larger ekklēsia. Every individual gathering of Christ-followers comprises an ekklēsia—no matter how small or large—and adding all these ekklēsiai together would constitute one ekklēsia in Rome.

And we can extrapolate further.

This all-inclusive ekklēsia is the meaning of the first definition in the LSJ above: the Church, as a body of Christians. In the context of 1Cor 11:22 Paul calls the ekklēsia at Corinth “the ekklēsia of God”. Note that, though Paul is writing to the Corinthians, this usage of ekklēsia is not specifically limited to those in Corinth. Like the implication in the opening of this epistle (1Cor 1:2), here in 11:22 (“Or do you despise the ekklēsia of God and humiliate those who have nothing?”) the phrase intends the entirety of the ekklēsia of God, to include Christ-followers outside Corinth. Stated another way, though Paul was addressing the ekklēsia in Corinth, he intends all Christ-followers in existence collectively—not strictly the Corinthians—evidenced by the additional modifier of God.

Thus, extrapolating even further, the one all-inclusive ekklēsia at Rome was to be included in the one all-inclusive ekklēsia at Corinth, both comprising a part of the one larger ekklēsia of God. And this should be expanded even more. Yet no matter how far geographically we broaden the scope, there is only one all-inclusive ekklēsia. Obviously, the larger we broaden it, the greater the number of people making up the ekklēsia. But, to reiterate, it is still one collective ekklēsia. This can even be expanded temporally to include all NT-era ekklēsiai (at Jerusalem, Rome, Corinth, Thessalonica, Galatia, etc.) in combination with all the ekklēsiai today (in North American, South America, Europe, Africa, Orient, etc.). All together these constitute the many-peopled one ekklēsia.

Now, in returning to Jesus’ words “my ekklēsia” in Matthew 16:18, we have a clearer idea of his intention. We would hardly think Jesus was referring to his ekklēsia as opposed to, say, Prisca and Aquila’s. Obviously—just like in 1Cor 11:22—Jesus was referring to all Christians collectively, rather than some group of Christians uniquely his own over against some other group or groups of Christians. An individual is either part of Jesus’ ekklēsia—the ekklēsia of God—or is not part of Jesus’ ekklēsia. And each and every ekklēsia individually is included in the one ekklēsia of Jesus—the entirety of Christ-followers collectively.

This collective, all-inclusive meaning stands behind the Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed of 381 (Ni-Con). The Ni-Con updated the earlier Nicene Creed (325).8 More importantly, Ni-Con defined the ekklēsia. Following is the pertinent portion:

[Pisteuomen] eis mian agian, katholikēn, and apolstolikēn ekklēsian

[We believe] in one holy, catholic, and apostolic ekklēsia.

We believe in one holy, universal, and apostolic ekklēsia.

The word “apostolic” refers to the fact that the ekklēsia dates back to the first century Apostles. Even the first person plural “we” embeds the all-inclusive intent. The only caveat is that each individual in the group must follow the tenets of the Creed (Trinity; Incarnation; Virginal conception/birth; Jesus’ death, burial, resurrection, and ascension; the Second Coming; one baptism).

The Ekklēsia Housed in Confusion

But somewhere along the way, post-NT era, ekklēsia shifted to “church”. This resulted in the understanding of the underlying NT word to mean “house” or “dwelling”, among other things. This conflation of ekklēsia as a body of Christians with its subsequent mutation as a building (for Christians)—or the fusing of the two—has created not a small amount of confusion. To illustrate the complexity of the issue, consider this meaning of ekklēsia as a building alongside the other multiple modern meanings of “church”.

In the 1983 unabridged Webster’s Dictionary definition for church is the following etymology:

Middle English chirche, cherche; Anglo-Saxon circe, cyrce; Late Greek kyriakon, a church, from Greek kyriakē (supply dōma, house), the Lord’s house, from kyriakos, belonging to the Lord or Master…9

In other words, “church” is not even derived from ekklēsia at all! It’s from kyriakos instead. Thus, this definition of “church” for ekklēsia is an anachronism by way of convoluted etymology. Stated another way, a word (“church”) from a much later time period is transported to the NT era (via kyriakos) and applied to a completely different word (ekklēsia) cargoing its multiplicity of modern meanings, and these meanings are almost entirely foreign to the original contexts.

To put mathematically: ekklēsia ≠ church! And, kyriakē ≠ ekklēsia.

Undoubtedly, this problem leads a reader to understand ekklēsia as any or all of the range of meanings found in “church” today (building, congregation, building with congregation, denomination, the entirety of Christians living and dead, clergy). In reading 1Cor 1:2 (to the church of God that is in Corinth), a modern reader might envision a large building on the corner of Main and 1st Streets with an accompanying marquee proclaiming “First Episcopal Church of Corinth”, where all Episcopalians living in Corinth would gather. But that’s far from historical accuracy.

If we go back to the NT usage of the relevant Greek words in the etymology above, we may be able to find the root of the problem. The Greek adjective kyriakos means something that pertains to the Lord (Jesus).10 It is used only twice in the NT. In the first instance (1Cor 11:20), the context specifically concerns the Lord’s Supper.11 In the second instance (Rev 1:10), the Lord’s Day,12 it refers to Sunday.13 The important thing to note is that the term kyriakos itself essentially means of the Lord, or the Lord’s.14 But the definition above uses the feminine form (kyriakē) rather than the masculine (kyriakos [also note: in the above etymology kyriakon is the neuter nominative form or masculine accusative form]). This use of the feminine form may relate to another possible connection just a bit below.

The parenthetical note in the etymology above (supply dōma, house) apparently indicates dōma is to be added to kyriakē in order to yield ~ the Lord’s house. But the word dōma means “housetop” or “roof” in the NT (Mt 24:17; Mk 13:15; Lk 5:19; Lk 17:31; Acts 10:9). Thus, it appears the two different meanings were fused together to form the one chirche, cherche, or “church”.

Another possible connection is the use of kyria—the feminine form of kyrios (Lord)—in 2 John 1:1 and 1:5. In the NT era, kyrios is used for a person having authority and would be rendered either “lord” or “master” (or, of course, “Lord” or “Master”). An equivalent for a female would be “lady”. In 2 John 1:1 the term is combined with eklektē—“chosen”, “elect”. In that context, it is to the elect lady and her children. It is possible (though impossible to confirm or disprove) to construe this as a figurative circumlocution for the bride of Christ.15 This may (or may not) go towards providing a basis for the etymology above in its use of kyriakē.

Even still, none of this answers why or how ekklēsia became “church” exactly. Like Darwinism, there’s something missing in the evolution.

There is one other possible connection. The Greek word for “a building”, “a structure” is domē.16 Though it does not occur in the NT, it is found in its verbal form in the compound word oikodomeō immediately preceding “my ekklēsia” in Matthew 16:18. This verb is a combination of the noun oikos (“house”, “dwelling”, “household”, “family”) and the verb domeō (“to build”, “to construct”). But in the context of Jesus’ words, this surely refers to a metaphorical building/constructing, not the building of a physical structure. Jesus was declaring he would ‘build’ a people-group by summoning from the larger group of all people.

And Jesus is still building it!

Further evidence of the confusion finds itself in all the modern dictionary meanings of ecclesia, ecclesial and ecclesiastical. It’s past time we reclaim the proper NT meaning!

Reconvening

Given the enquiry here, how should we translate ekklēsia? Negatively, as noted in the beginning, I propose we heave “church” to the linguistic landfill. Positively, I suggest we substitute congregation in all places “church” is currently found in Scripture. The three Acts 19 occurrences could be assembly, in keeping with most versions’ current use of the term there.

Using congregation instead of “church” might go a long way toward alleviating both confusion and denominational divisions. True Christ-followers comprise one ekklēsia. Separate, individual congregations, but one universal (catholic) ekklēsia!

Just like we meet (verb) at our meeting (noun), we congregate at our congregation. And we are not a congregation unless we congregate. Assembly required!

We congregate when we attend services or when we attend Bible studies—whether at a ‘church’ building, in someone’s home, or any other place. It could possibly be understood that we assemble when speaking on the phone with a Christian brother or sister. Or maybe even when conversing via email.

Postscript

I began writing this article well before the current health issue and the resulting socio-political environment surrounding it. Thus, I am not intending to make any sort of socio-political statement with this. However, in light of the current situation, I think it might be best that every individual ekklēsia proceed as led, considering local regulations and recommendations in balance with Hebrews 10:25, Romans 13:1—8 and 1Peter 2:13—17.

Godspeed.

__________________________

1 See “κλῆσις” in F. W. Danker, The Concise Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament (Chicago, IL: Chicago, 2009), p 202.

2 The Textus Receptus—the Greek text underlying the KJV and NKJV—includes the term at Matthew 20:16, appending the verbiage found in Matthew 22:14: πολλοὶ γάρ εἰσι κλητοί, ὀλίγοι δὲ ἐκλεκτοί, polloi gar eisi klētoi, oligoi de eklektoi, for many are called but few are chosen.

3 Though the main reason for the title of this section is to refute “church” as a meaning for ekklēsia, a subsidiary reason is to debunk the notion that ekklēsia is some exclusive term made up of its prefix and the verb kaleō, as if the term were coined strictly for Christians. Such an understanding seems implied by R. C. Sproul, someone whose teachings I generally enjoy: Ekklesia: The Called-Out Ones. We must do better than this. Tangentially, in view of the contents at the link, I might have asked Sproul about Judas Iscariot: Was he not part of the Twelve? Does this not imply he was one of the called (klētos)? How do we square Sproul’s doctrine of ‘election’ with Matthew 22:14 (and Matthew 20:16 TR—see note 2 above)?

4 Though inferences can certainly be drawn from its conclusions.

5 The Greek of Romans 16:5 (the 2nd sub-definition) is actually τὴν κατ᾿ οἶκον αὐτῶν ἐκκλησίαν, tēn kat’ oikon autōn ekklēsian. In paraphrase, the LSJ changed it to the nominative instead of the accusative and the personal pronoun (αὐτῶν) to the indefinite (τινος).

6 My own translation, as all here.

7 Likely founded by Paul’s missionary efforts (cf. Romans 16:10-11).

8 To include a defining of the Holy Spirit, which had barely been mentioned in the 325 version.

9 Jean L. McKechnie, Webster’s New Twentieth Century Dictionary of the English Language Unabridged, 2nd ed. (New York, NY: Simon and Schuster, 1983), p 324. I am unfamiliar with Late Greek, but in the NT, kyriakon is the accusative form of kyriakos (as found in 1Cor 11:20; see below), but it’s also a neuter nominative form (not used in NT). Kyriakē is the feminine nominative form (again, not used in NT).

10 “κυριακός”, in W. Bauer, F. W. Danker, W. F. Arndt, and F. W. Gingrich, A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament and Other Early Christian Literature, 3rd. ed. (Chicago, IL: Chicago, 2000), p 576.

11 In the accusative/direct object case: kyriakon deipnon.

12 In the dative/indirect object case: tȩ̄ kyriakȩ̄ hēmera̧.

13 David Aune, Revelation 1—5, Word Biblical Commentary, Gen. Eds. D. A. Hubbard, G. W. Barker (Dallas, TX: Word Books), pp 83—84.

14 “κυριακός” in Danker, p 210.

15 See “κυρία” in Danker, p 210; cf. Judith M. Lieu, I, II, & III John (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 2008), pp 240—42, 248—52.

16 Maybe the Webster’s “dōma” in the etymology above is in error?

It's Appropriate To Share:

![]() On a number of levels, I find this icon fascinating![1]

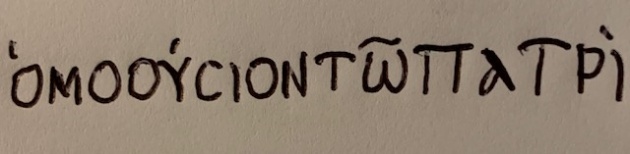

On a number of levels, I find this icon fascinating![1] The accent over the first omicron (O) is what is known as the rough breathing mark, indicating to sound the vowel with a prepended English “H” (“ha”). This is the reason for its transliterated spelling homoousion.

The accent over the first omicron (O) is what is known as the rough breathing mark, indicating to sound the vowel with a prepended English “H” (“ha”). This is the reason for its transliterated spelling homoousion.![]() ΟΜΟΟΥCΙΟΝΤШΠАΤΡΙ

ΟΜΟΟΥCΙΟΝΤШΠАΤΡΙ![]()

Recent Comments