Fishers of Persons

August 26, 2018 2 Comments

Now as He was walking along the Sea of Galilee, Jesus saw two brothers—Simon (the one called Peter) and his brother Andrew—casting nets into the lake, for they were fishers. And He said to them, “Come follow Me, and I will make you fishers of persons1” (Matthew 4:18-19).

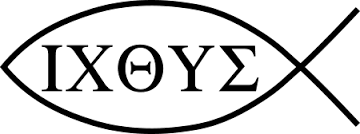

Our subject verses, Matthew 4:18-19, along with the parallels Mark 1:16-17 and Luke 5:1-11 (cf. John 1:35-42), are among the number of New Testament (NT) references to fishing. Most Christians (and non-Christians) in the West are aware of the fish symbol used to signify Christianity. Nowadays it can be found on cars, various kinds of jewelry, etc. But what does the “Jesus fish”, the ichthys (or ichthus) symbolize exactly? Why and when was it first used?

credit: Wikimedia Commons

Possible OT and Jewish Background

While Jesus may have seized the opportunity to use the “fishers of persons” comparison simply because Simon Peter and Andrew were fishermen, it seems probable that this metaphor was also chosen to counter contemporary negative Jewish fishing metaphors. If so, the effect would have been to contrast those metaphors of God’s judgment with these fishers who will “pluck human beings out of the net of Satan and transfer them securely into the net of God”2 (cf. Matthew 13:47-48).

The Old Testament (OT) provides a number of metaphorical references to fishing, the majority relating to judgment:

- The LORD (YHWH) sending ‘fishermen’ to catch the wicked Israelites (Jeremiah 16:16)

- YHWH using the Babylonians to capture wayward Israel by ‘hook’ and ‘net’ (Hab. 1:14-15)

- God threatening to take away the unrighteous of Israel via ‘fishhook’ (Amos 4:2)

- YHWH equating Pharaoh and his people to fish who will be hooked (Ezek. 29:3-5; cf. 38:4)

- Various peoples being caught by ‘fishnet’, symbolizing God’s judgment (Ps. 66:11; Ezek. 32:3).

Closer to the time of Christ, the Qumran community, via the Dead Sea Scrolls, provided commentary (pesher) on Isaiah 24:17, illustrating how YHWH judges the disobedient by sending Belial (Satan) to ensnare them:

Belial will be sent against Israel, as God has said by means of the prophet Isaiah, son of Amoz, saying: ‘Panic, pit and net against you earth-dwellers’. Its explanation: They are Belial’s three nets about which Levi, son of Jacob spoke, in which he catches Israel and makes them appear before them like three types of justice. The first is fornication; the second, wealth; the third, defilement of the Temple. He who eludes one is caught in another and he who is freed from that is caught in another (Damascus Document [CD IV:13-19]).3

Yet, amidst all the negative fishing imagery in the OT, Ezekiel 47:9-10 speaks of a new Temple (cf. Rev. 22:1-5), one with a river which will provide abundant life to fish (and all other creatures, vegetation, and trees receiving sustenance from it—Ezek. 47:11-12):

9 And it will come to be that every living creature that swarms wherever the river flows will live; and there will be a great multitude of fish, because this water will flow there, healing the seawater—making it freshwater. Everything will live where this water flows. 10 And it will come to be that fishers will stand on its banks: from En Gedi to En Eglaim there will be places to spread the nets. There will be many species of fish, just like the fish of the Mediterranean Sea—a multitude of many kinds of fish.

Jesus of Nazareth, the Jewish Messiah, came “to preach the good news to the poor…to proclaim freedom to the captives, renewed sight for the blind, and to relieve the oppressed” (Luke 4:18), in fulfillment of Isaiah 61:1!

NT usage of ICHTHYS, Fish

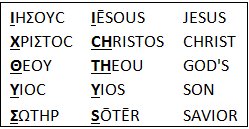

The Greek word for “fish” is ιχθυς, which is transliterated—exchanging each Greek letter for corresponding English letters—ichthys or ichthus. The Greek letters in the previous sentence are in miniscule minuscule, like our lower case letters. In majuscule, akin to our capital letters, the word is ΙΧΘΥΣ—as in the figure below—or, transliterated, ICHTHYS. The earliest Greek NT manuscripts are in majuscule; the minuscule would develop later. ΙΧΘΥΣ is found twenty times in the NT. (The word for “fisher” is the unrelated ἁλιεύς, halieus.)

Since the English transliteration has seven characters to the Greek five, further explanation seems necessary. The second and third Greek letters are digraphs in English—two letters representing one sound—whereas they are indicated by one symbol in the Greek. Here are the Greek-to-English correlations:

I, ι (iota) = I, i

X, χ (chi) = CH, ch

Θ,θ (theta) = TH, th

Υ, υ (upsilon) = Y, u/y

Σ/C, σ/ς (sigma) = S, s

credit: Wikimedia Commons

While Mark 1:16-17 is nearly identical to our subject verses Matthew 4:18-19, the good doctor Luke expands the incident considerably. Luke’s Gospel records the first great catch of fish, chronologically, in the NT (Luke 5:1-10). Simon Peter, after fishing all night and coming up empty, is instructed by Jesus to go back out into the deep water. After expressing a bit of reluctance initially, Simon relents, catching so many fish that he needed another boat to help retrieve them all!

Apparently feeling ashamed for his lack of faith, Peter fell at Jesus’ knees, saying, “Away from me, for I am a sinful man, O Lord!” Sensing the feelings of awe within Peter, Andrew, James, and John, Jesus tells them to not be afraid, for they were now to catch people. Certainly, this first great catch of fish must be symbolically linked to their future great catches as “fishers of persons”.

The remaining NT passages containing ΙΧΘΥΣ are:

- “…if he asks for a fish, will you give him a snake?” (Matthew 7:10; Luke 11:11)

- The miraculous feeding of the five thousand (Matthew 14:13-22; Mark 6:32-44; Luke 9:10-17; John 6:1-13

- The miraculous feeding of the four thousand (Matthew 15:32-29; Mark 8:1-10)

- Paying the “Temple tax”, via the first fish Peter was to catch, in which would be a silver coin (statēr) worth four drachmae (Matthew 17:27)

- The broiled fish that was given to the risen Jesus (Luke 24:42)

- The account of the risen Jesus instructing the disciples to again throw out their net, a near recapitulation of the first great haul of fish, excepting their lack of hesitation this time (John 21:6-14)

- The Apostle Paul comparing the flesh of humans with the different flesh of animals, birds, and fish as he discusses the new spiritual body (1 Corinthians 15:39)

There is one more Scripture relevant here—though it does not contain ichthys, it does contain the Greek word for “dragnet”. It is the Parable of the Net (Matthew 13:47-50), which is a mixture of the negative OT judgment metaphor and a different take on the NT ‘fishers of persons’ analogy, in the form of eschatological (end times) judgment/salvation (cf. Matthew 13:30, 40-42; Revelation 14:14-20)

Use of ΙΧΘΥΣ in early Christianity

In the first century AD, many Christian converts met in private homes.4 After the Christian faith gained wider acceptance, buildings were erected specifically for worship.5 These early places of worship were unadorned and plain, for Christians were concerned about possibly falling prey to idolatry.6

In these early days, one would not find drawings or sculptures of Christ; however, eventually, symbols representing our Lord and our faith would be made.7 Rather than fashioning a likeness of Jesus’ human form, “they made a figure of a shepherd carrying a lamb on his shoulders, to signify the Good Shepherd who gave his life for his sheep”8 (John 10:11). The Messiah was also represented symbolically as a lamb.9 Other Christian symbols used were: a dove to represent the Holy Spirit; a ship, to signify the Church, the ark of salvation, sailing towards heaven; a lyre, to represent joy; an anchor, to symbolize hope; and, “a fish, which was meant to remind them of their having been born again in the water at their baptism”.10

These symbols began to be used on everyday items at home, such as lamps, vases, rings, bowls, wall-hangings and the like.11 Fish symbols were also found in the Roman catacombs in pictures with bread and wine—in some the fish is swimming in the water with a plate of bread and a cup of wine on its back, evidently alluding to the Last Supper or Eucharist.12 The oldest known ΙΧΘΥΣ-monument, the Cœmeterium Domitillae (cemetery of Flavia Domitilla) in the catacombs, is dated perhaps as early as the late first century, to the middle of the second.13 This one depicts three persons with three loaves of bread and one fish,14 a likely reference to the miraculous feedings.

It is unknown when, but someone ingeniously invented an acrostic (backronym) based on the letters of ΙΧΘΥΣ: ΙΗΣΟΥΣ ΧΡΙΣΤΟΣ ΘΕΟΥ ΥΙΟΣ ΣΩΤΗΡ (IĒSOUS CHRISTOS THEOU YIOS SŌTĒR), which translates to JESUS CHRIST, GOD’S SON, SAVIOR.

ΙHΣΟΥΣ = IĒSOUS = JESUS

ΧΡΙΣΤΟΣ = CHRISTOS = CHRIST

ΘΕΟY = THEOU = GOD’S

ΥΙΟΣ = YIOS = SON

ΣΩΤΗΡ = SŌTĒR = SAVIOR

Legend has it that during the early stages of Christianity and its attendant persecution, a Christ-follower, upon meeting someone whom they thought could be a fellow Christian, would seemingly nonchalantly draw one arc of the ΙΧΘΥΣ in the sand.

One arc of ΙΧΘΥΣ

If the other individual responded by drawing the intersecting arc, thereby completing the fish symbol, they would each know the other was a fellow sojourner in the faith.

Completed ΙΧΘΥΣ

Conversely, if the other individual was not a Christ-follower, the gesture would be viewed as mere doodling and not reveal the faith-belief of the original drawer.15

According to Schaff, the ICHTHYS was the symbol most used.16 “It was the double symbol of the Redeemer and the redeemed”.17 Tertullian (ca. 155-225 AD), in his De Baptismo (On Baptism), makes this connection explicitly:

Happy is our sacrament of water, in that, by washing away the sins of our early blindness, we are set free and admitted into eternal life! A treatise on this matter will not be superfluous; instructing not only such as are just becoming formed (in the faith), but them who, content with having simply believed, without full examination of the grounds of the traditions, carry (in mind), through ignorance, an untried though probable faith…But we, little fishes (pisciculi [ED: Latin]), after the example of our ΙΧΘΥΣ Jesus Christ, are born in water, nor have we safety in any other way than by permanently abiding in water…18

In the following, Clement of Alexandria (ca. 150—215 AD) instructs fellow believers to steer away from idols, as he delineates these from the symbols described earlier. Note that he alludes to the ‘fishers of persons’ analogy:

And let our seals be either a dove, or a fish, or a ship scudding before the wind, or a musical lyre, which Polycrates used, or a ship’s anchor, which Seleucus got engraved as a device; and if there be one fishing, he will remember the apostle, and the children drawn out of the water. For we are not to delineate the faces of idols, we who are prohibited to cleave to them; nor a sword, nor a bow, following as we do, peace; nor drinking-cups, being temperate.19

In a somewhat convoluted mixing of metaphors linguistic devices, Origen (ca. 185-254) takes the miracle of the fish with the coin to pay the Temple tax and turns this into an allegory of Peter as fisher of persons:

As then, having the form of that slave, He pays toll and tribute not different from that which was paid by His disciple; for the same statēr sufficed, even the one coin which was paid for Jesus and His disciple. But this coin was not in the house of Jesus, but it was in the sea, and in the mouth of a fish of the sea which, in my judgment, was benefited when it came up and was caught in the net of Peter, who became a fisher of men, in which net was that which is figuratively called a fish, in order also that the coin with the image of Caesar might be taken from it, and that it might take its place among those which were caught by them who have learned to become fishers of men…20

The following comes from an early Christian novel (ca. 3rd to 4th century AD) Acts of Xanthippe, Polyxena, and Rebecca (part of what is known as New Testament Apocrypha). Note the reference to ‘fishers of persons’, and the possible allusion to the Parable of the Net (Matthew 13:47-52):

Thou hast sought me [Xanthippe], lowly one, having the sun of righteousness in my heart. Now the poison is stayed, when I have seen thy [Paul’s] precious face. Now he that troubled me is flown away, when thy most beautiful counsel has appeared to me. Now I shall be considered worthy of repentance, when I have received the seal of the preacher of the Lord. Before now I have deemed many happy who met with you, but I say boldly that from this time forth I myself shall be called happy by others, because I have touched thy hem, because I have received thy prayers, because I have enjoyed thy sweet and honeyed teaching. Thou hast not hesitated to come to us, thou that fishest the dry land in thy course, and gatherest the fish that fall in thy way into the net of the kingdom of heaven.21

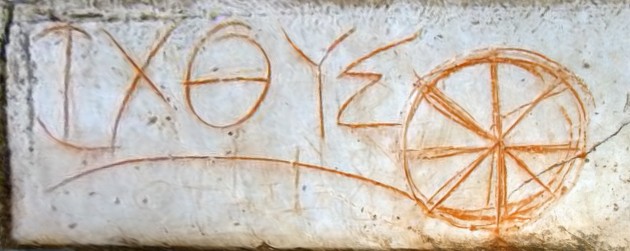

Below is an ΙΧΘΥΣ inscription found in Ephesus (modern-day Turkey). Note the 8-spoked wheel. This is made by taking the letters, one at a time, superimposing each one over the other(s). The top and bottom of the iota must be suitably curved in order to fashion the wheel.

Early Christian inscription with the Greek letters “ΙΧΘΥΣ” carved into marble in the ruins of the ancient Greek city of Ephesus at Turkey

In the Sibylline Oracles, Book 8, verses 284-330 (Greek text 217-250)–dated ca. 3rd to 5th century AD–an acrostic is formed from the first letter of the first word in each line, resulting in (in English): JESUS CHRIST, GOD’S SON, SAVIOR, CROSS (ΙΗΣΟΥΣ ΧΡΙΕΣΤΟΣ ΘΕΟΥ ΥΙΟΣ ΣΩΤΗΡ ΣΤΑΥΡΟΣ [IĒSOUS CHRIESTOS THEOU YIOS SŌTĒR STAUROS]). Similarly, Augustine, in his de Civitate Dei (xviii, 123) forms an acrostic in the same manner, but without “Cross”—spelling out the ΙΧΘΥΣ (ΙΗΣΟΥΣ ΧΡΙΣΤΟΣ ΘΕΟΥ ΥΙΟΣ ΣΩΤΗΡ).

Evidence seems to indicate that the ΙΧΘΥΣ-symbol fell into disuse prior to the middle of the fourth century.22 It was apparently revived on or just before 1970, during the “Jesus movement”. The ICHTHUS is quite prevalent today, at least in the West.

—————————

1 “Persons” translates the Greek ἄνθρωπος (anthrōpos), here in the plural, the word from which we get anthropology, the study of humankind. My translation “persons”, as opposed to “people”, goes against current norms, for the term is usually confined to formal or legal contexts, such as “missing persons” or “persons of interest”. However, this is precisely, why I chose the term! Who are we to ‘fish’ for? According to Paul’s list in First Corinthians 6:9-10, we are to fish for thieves, swindlers, adulterers (yes, adultery is still on the books as a crime in some states, and it is certainly contrary to Mosaic Law), slanderers, etc., aka “persons of interest”, until they are ‘convicted’. And these were among those converted in the 1st century. Yet, I do not wish to limit the meaning in such a manner, as this term is simply a lesser used plural of “person”. Thus, consider my usage here as a synonym to “people”, but with the added underlying sense of individuals with less-than-optimum character. And who—besides Jesus—does not fit that description anyway? In the sense that “there is none righteous, not even one” (Romans 3:12; cf. 3:20; Psalm 14:1-3), we are all “persons of interest”! All such persons need to be ‘caught’. Moreover, the Day of the Lord will only come when all “missing persons” are ‘found’ (2 Peter 3:8-10).

2 Joel Marcus, Mark 1–8, The Anchor Yale Bible (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1974), p 184.

3 Florentino Garci̒a Marti̒nez, The Dead Sea Scrolls Translated: The Qumran Texts in English, 2nd ed., transl. Wilfred G. E. Watson (Netherlands: Brill, Leiden/Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1996), p 35. Cf. 1QH 3:26

4 James C. Robertson, Sketches of Church History: From A.D. 33 to the Reformation, Accordance electronic ed. (London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, 1912), p 86; Larry W. Hurtado, Destroyer of the gods: Early Christian Distinctiveness in the Roman World, (Waco, TX: Baylor University Press, 2016), p 3.

5 Robertson, Sketches, p 86.

6 Ibid.; Philip Schaff, Apostolic Christianity, History of the Christian Church 1; Accordance electronic ed. 8 vols.; (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1910), paragraph 799 / (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 2011), p 168; Philip Schaff, Ante-Nicene Christianity, History Of The Christian Church 2; Accordance electronic ed. 8 vols.; (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1910), paragraph 6357 / (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 2011), p 267. Hereafter, references to Schaff will be dual credited as the Accordance paragraph / the Hendrickson page(s).

7 Robertson, Sketches, pp 86-87; Schaff, Ante-Nicene Christianity, para. 6358-91 / pp 267-68.

8 Robertson, Sketches, pp 86-87.

9 Schaff, Apostolic Christianity, para. 799 / p 168.

10 Robertson, Sketches, p 87.

11 Schaff, Ante-Nicene Christianity, para. 6358-59 / p 268; Cf. Schaff, Ante-Nicene Christianity, pp 267-281, 867-868; Alexander Roberts, James Donaldson, and A. Cleveland Coxe, eds., Fathers of the Second Century: Hermas, Tatian, Athenagoras, Theophilus, and Clement of Alexandria, Ante-Nicene Fathers, ANF II; Accordance electronic ed. 9 vols.; (New York: Christian Literature Company, 1885), paragraph 12131 [Elucidations on Clement of Alexandria’s “The Instructor (Paedagogus)” Book II, Chapter III: On Costly Vessels].

12 Schaff, Ante-Nicene Christianity, para. 6403, 9210 / pp 279, 280 (in footnote 2).

13 Ibid.

14 Ibid.

15 “Fish Symbol”, ReligionFacts.com, 18 May, 2017, Web, as accessed 25 Aug, 2018. <www.religionfacts.com/fish>

16 Schaff, Ante-Nicene Christianity, para. 6403 / p 279.

17 Ibid.

18 Alexander Roberts, James Donaldson, and A. Cleveland Coxe, eds., Latin Christianity: Its Founder, Tertullian, ANF III; Accordance electronic ed. 9 vols.; (New York: Christian Literature Company, 1885), paragraph 28175 [Tertullian “On Baptism” Chapter I. Introduction: Origin of the Treatise].

19 Roberts, Donaldson, & Coxe, eds., Fathers of the Second Century, ANF II, para. 11707 [Clement of Alexandria “The Instructor (Paedagogus)” Book III, Chapter XI: A Compendious View of the Christian Life].

20 Alexander Roberts, James Donaldson, and A. Cleveland Coxe, eds., The Gospel of Peter, the Diatessaron of Tatian, the Apocalypse of Peter, the Visio Pauli, the Apocalypses of the Virgin and Sedrach, the Testament of Abraham, the Acts of Xanthippe and Polyxena, the Narrative of Zosimus, the Apology of Aristides, the Epistles of Clement, Origen’s Commentary on John, Books I–x, and Commentary on Matthew, Books I, Ii, and X–xiv, ANF IX; Accordance electronic ed. 9 vols.; (New York: Christian Literature Company, 1885), paragraph 79992 [Origen “From the Second Book of the Commentary on the Gospel According to Matthew”, Book XIII.10].

21 Alexander Roberts, James Donaldson, and A. Cleveland Coxe, eds., The Gospel of Peter, the Diatessaron of Tatian, the Apocalypse of Peter, the Visio Pauli, the Apocalypses of the Virgin and Sedrach, the Testament of Abraham, the Acts of Xanthippe and Polyxena, the Narrative of Zosimus, the Apology of Aristides, the Epistles of Clement, Origen’s Commentary on John, Books I–x, and Commentary on Matthew, Books I, Ii, and X–xiv, ANF IX; Accordance electronic ed. 9 vols.; (New York: Christian Literature Company, 1885), paragraph 77323 [“Life and Conduct of the Holy Women Xanthippe, Polyxena, and Rebecca”].

22 Schaff, Ante-Nicene Christianity, para. 6404 / p 280.

Recent Comments